Against Frictionless

Lessons from An Ecosystem Helping Small Cheese Producers Survive in France

Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin - Still Life with Copper Pot, Cheese and Eggs

c.1730-1735

“How can you govern a country that has two hundred and forty-six varieties of cheese?”

Charles De Gaulle

The French love of cheese is deeply encoded into the national psyche.

It is not simply a food preference, but a symbol of Frenchness itself: of France, of continuity, of shared time and ritual.

And yet the cheese itself has changed almost beyond recognition over the past seventy years.

In that time, French cheese has been aggressively pasteurized, industrialized, standardized, marketed, and branded.

What was once a fragile, variable, place-bound practice has been reshaped into a managed system optimized for safety, abundance, and consistency.

This transformation happened through regulation and market logic.

A bureaucratic and capitalist land grab disguised as protection and progress.

Consumers are satisfied.

Industrial cheese is abundant, available, affordable, and “good enough.”

It reliably does the job.

But something important has been lost along the way.

Not cheese itself, but the conditions that once gave it meaning: risk, time, microbial life, human judgment, and difference.

Taste did not disappear, but taste sophistication eroded, because discernment was no longer required.

“Everyday food is not the object of constant arbitration.

It rests on incorporated routines that make transformations difficult to perceive.”

Jean-Pierre Poulain, Sociologies de l’alimentation

There have been loud critics of this erosion, figures like Périco Légasse, who has long accused France’s appellation system of being hollowed out by industrial interests, arguing that names were preserved even as the standards they were meant to protect were progressively eroded.

But the most consequential resistance has not been polemical.

It has been quiet, practical, and sustained.

The real pushback has come from people who do more than they talk.

Producers who refuse simplification even when it costs them their appellation.

Affineurs (cheese agers) like Hervé Mons of Fromagerie Mons, who absorb risk so that difficult cheeses and demanding practices can continue to exist.

Chefs who specify farms rather than brands.

Cheesemongers who insist on education rather than reassurance.

They ensure the craft, taste, and traditional means of production that once defined French cheese remain alive.

In a culture content with “sufficient” cheese, they insist that some standards must remain demanding, even when no one is asking for it.

The most extreme example of the resistance movement is the “Salers Tradition”

Géraud Delorme is a Salers Tradition fermier and cheesemaker who farms near Recoules in the Auvergne on land his family has worked since the early nineteenth century.

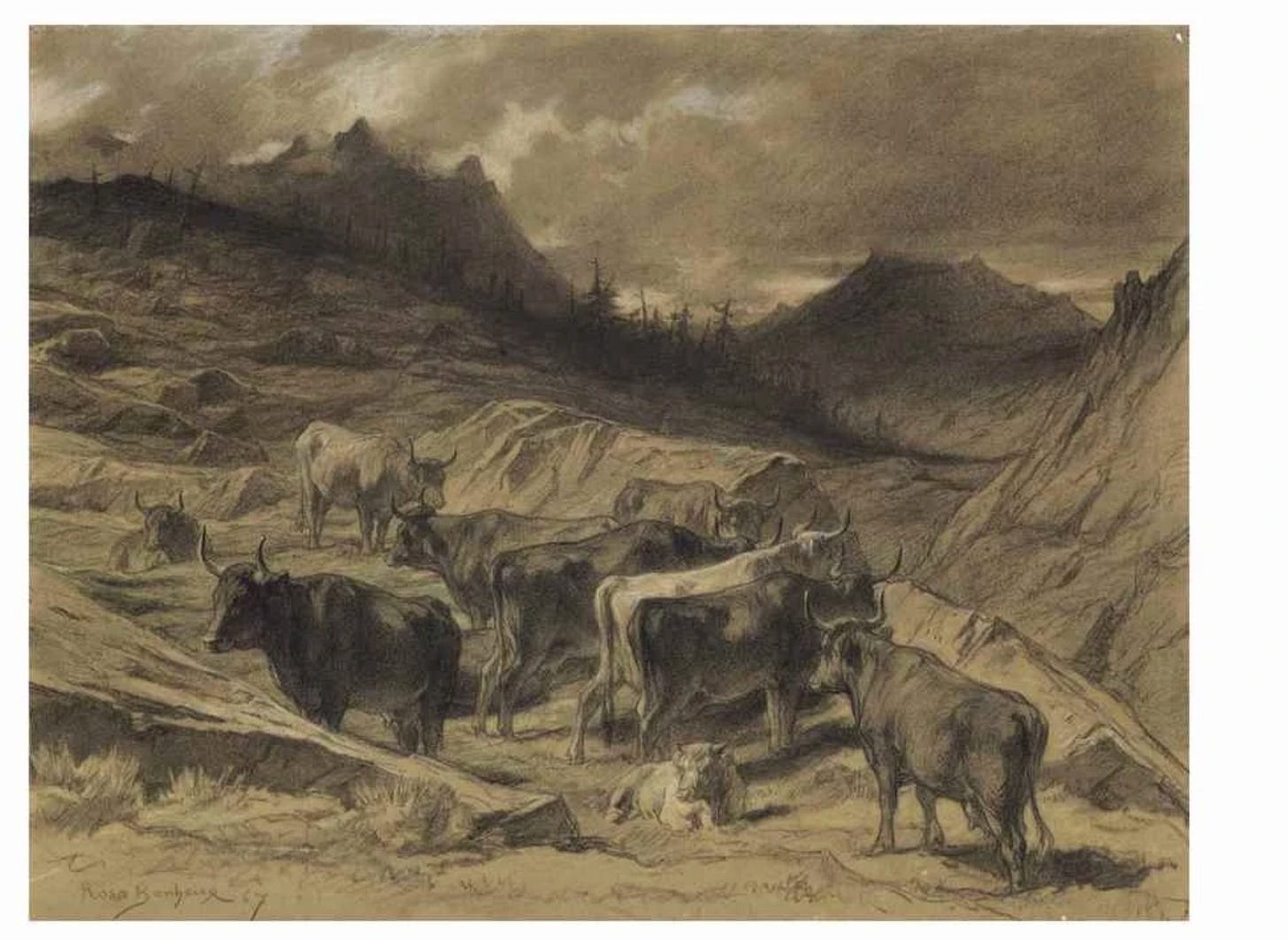

Rosa Bonheur- Salers cattle in the Auvergne, 1867

Delorme works with Salers cows, a breed that refuses to cooperate with modern efficiency.

A Salers cow won’t give milk unless her calf is present.

The calf stimulates milk flow, cleans and transfers lactic acid bacteria from its mouth directly onto the udder. Those bacteria pass into the milk and become the foundation of the cheese.

Nothing is added later.

There are no commercial cultures.

No correction downstream.

The milk, still warm, is poured directly into a wooden vat, a gerle with a porous surface that carries a living microbiome.

If the vat is too large, the balance fails. If chemicals are used to clean it, the system collapses. Each day, the vat is washed only with whey from the previous make, preserving the microbial continuity.

Production is seasonal and limited. One day’s milking becomes one wheel. There is no blending across days, there is no averaging out variation.

When the weather turns or pasture burns, production slows or stops.

What Delorme produces is not simply rare cheese. It is cheese made at the edge of failure.

Every step increases exposure: to weather, to animal health, to microbial imbalance, to time.

As climate volatility increases, grass fails more often. Institutions respond by loosening standards, allowing more substitution to keep production going.

The cheese survives. The category endures.

But the conditions that make Salers Tradition legible, the pasture, seasonality, and interruption, can be quietly eroded.

Géraud Delorme is one of a small number of producers whose cheese is handled by Fromagerie Mons.

Mons began as a market stall selling local cheeses.

Today, Mons is a family-run enterprise with ageing caves, retail shops, and a school.

Mons buys Delorme’s cheese young, paying for it upfront. The cheese is then aged in Mons’s caves, evaluated over months, and released only when it is ready or not released at all.

Mons could be described as the spine that helps support the tiny producers.

While Mons is not the only cheese ager in France, it’s one of the most significant.

If Mons is the spine, the ecosystem has other important members including; chefs and cheesemongers all dedicated to keeping the tradition of real cheese alive.

Laguiole is famous for its knives, built for farmers and herdsmen who needed a tool that could cut bread, carve wood, or bleed an animal.

Chef Michel Bras is from Laguiole.

What distinguishes Bras from his peers is that he owes little to the culinary establishment. He is largely an autodidact. He did not go to Paris or Lyon to apprentice under the “great masters.” He stayed in Laguiole, learning from his mother, Mémé Bras, and from the land.

For decades, Bras began his days not in the kitchen, but on the trails. He is a runner. He did not run for fitness; he ran to inhabit the landscape.

Moving through the high plateau in silence, breathing the fog, noticing wild herbs, grasses, and flowering plants, he internalized the terrain. Because he was self-taught, he had no rigid techniques to unlearn.

He cooked what he observed.

Bras is known for his versions of Aligot, the region’s foundational dish: mashed potatoes with fresh Tomme de Laguiole cheese.

It is here, in the stretching of aligot, that Bras’s philosophy takes shape. The dish is a litmus test. If the cheese is made from milk produced by cows fed silage or kept indoors, the structure collapses.

The aligot breaks. For the ribbon to stretch, sometimes dramatically, the cheese must be right.

Bras learned early that he could not “chef” his way out of compromised ingredients.

He had to submit to them.

This philosophy, valuing lived rhythm over external pressure, reached a public inflection point with his son, Sébastien.

After maintaining three Michelin stars for nearly two decades, Sébastien Bras asked in 2017 for the restaurant to be removed from the Michelin Guide. He wanted to cook without the constant pressure of inspection. He wanted the freedom to experiment, to fail, and to align the kitchen with its own logic rather than an external standard.

The decision stunned the culinary world. But within the Bras family, it was consistent.

Just as a cheesemaker accepts that a cheese may fail, the chef reclaimed the right to work without guarantees.

If Michel Bras is the hermit of the plateau, Marie Quatrehomme is the diplomat of the city.

While affineurs like Hervé Mons operate at an international scale, Quatrehomme occupies a distinct role in the French imagination.

In 2000, she became the first woman to earn the title of Meilleur Ouvrier de France (Master Craftsman) in the fromager category.

Her shops in Paris are not just stores; they are translation centers.

Quatrehomme and now her daughter Nathalie work to explain absence and to curate variation.

When a Salers producer suspends production because summer grass has failed, or when a wheel of Beaufort develops a fault, it is Quatrehomme who explains.

Her skill lies in discerning which irregularities are defects and which are expressions of character.

By teaching customers to accept cheese that is stronger, milder, firmer, or softer than last month, she preserves a market for variability.

This is quiet work. It is also essential.

A cow in the Massif Central eating grass that changes with the weather.

A producer refusing commercial cultures.

A cook running through the hills, learning by attention.

A son returning Michelin stars.

A cheesemonger refusing to smooth her counter.

This is not just food culture. It is a form of resistance.

We live in an era engineered for frictionlessness.

We expect strawberries in January and cheese that tastes identical across continents.

We have built systems to eliminate surprise.

The people in this story are the sand in that machinery.

They insist through their labor that efficiency is not the highest value.

That variation is not a flaw.

That reality, uneven and demanding, is the point.

This is not about nostalgia, purity, or even cheese.

It is about what we choose to carry forward and what we allow to disappear quietly in the name of ease.

As Hervé Mons has said,

”Si ces fromages disparaissent, ce n’est pas seulement un goût que l’on perd, c’est un savoir-faire, un paysage, une culture. “

What gives that resistance a future is not nostalgia, but education that’s made universal, public, and free.

In France, children are still taught how to taste through éducation au goût, embedded in the national school system and reinforced daily in the cantine, where difference is explained rather than smoothed away.

In 2025, as optimization systems grow powerful enough to erase variation without detection, this matters more than ever.

Because once the capacity to taste is lost, loss itself becomes invisible and disappearance no longer requires consent.